GAO's publish survey about facial recognition technology (FRT) activities

Facial recognition—a type of biometric technology—mimics how people identify or verify others by examining their faces. Recent advancements have increased the accuracy of automated FRT resulting in increased use across a range of applications. As the use of FRT continues to expand, it has become increasingly important to understand its use across the federal government in a comprehensive way.

GAO was asked to review the extent of FRT use across the federal government. This report identifies and describes (1) how agencies used FRT in fiscal year 2020, including any related research and development and interactions with non-federal entities, and (2) how agencies plan to expand their use of FRT through fiscal year 2023.

GAO surveyed the 24 agencies of the Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990, as amended, regarding their use of facial recognition technology. GAO also interviewed agency officials and reviewed documents, such as system descriptions, and information provided by agencies that reported using the technology.

Recent advancements in facial recognition technology have increased its accuracy and its usage. Our earlier work has included examinations of its use by federal law enforcement, at ports of entry, and in commercial settings.

For this report, the GOA surveyed 24 federal agencies about their use of this technology.

- 16 reported using it for digital access or cybersecurity, such as allowing employees to unlock agency smartphones with it

- 6 reported using it to generate leads in criminal investigations

- 5 reported using it for physical security, such as controlling access to a building or facility

- 10 said they planned to expand its use

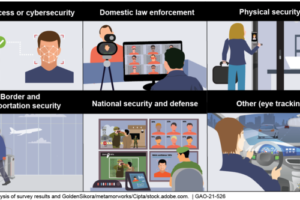

In response to GAO's survey about facial recognition technology (FRT) activities in fiscal year 2020, 18 of the 24 surveyed agencies reported using an FRT system, for one or more purposes, including:

Digital access or cybersecurity. Sixteen agencies reported using FRT for digital access or cybersecurity purposes. Of these, 14 agencies authorized personnel to use FRT to unlock their agency-issued smartphones—the most common purpose of FRT reported. Two agencies also reported testing FRT to verify identities of persons accessing government websites.

Domestic law enforcement. Six agencies reported using FRT to generate leads in criminal investigations, such as identifying a person of interest, by comparing their image against mugshots. In some cases, agencies identify crime victims, such as exploited children, by using commercial systems that compare against publicly available images, such as from social media.

Physical security. Five agencies reported using FRT to monitor or surveil locations to determine if an individual is present, such as someone on a watchlist, or to control access to a building or facility. For example, an agency used it to monitor live video for persons on watchlists and to alert security personnel to these persons without needing to memorize them.

Ten agencies reported FRT-related research and development. For example, agencies reported researching FRT's ability to identify individuals wearing masks during the COVID-19 pandemic and to detect image manipulation.

Furthermore, ten agencies reported plans to expand their use of FRT through fiscal year 2023. For example, an agency plans to pilot the use of FRT to automate the identity verification process at airports for travelers.